The History of SAORI

Misao Jo (1913–2018)

Misao Jo did not have any conventional qualifications, mentors or desires for materialism. Instead, she had her dream of global harmony, passion for inspiring humanity and creativity, and spirited commitment to challenging and expanding the status quo.

Misao Jo, 2001.

“The Ikebana Incident”

Many people often asked Misao how she came to develop SAORI, wondering how her life as a housewife and mother led to such a revolutionary approach to thinking and influencing others. In fact, it is important to acknowledge, as Misao herself did, that the foundation for SAORI actually began more than thirty years earlier with her experiences with ikebana, the Japanese art form of flower arrangement. Soon after her marriage at the age of 25, Misao and her husband were expecting a visitor at their home. Having studied ikebana for almost eight years and obtaining an instructor’s license, Misao decided to arrange flowers to welcome their friend. But in the process, she suddenly found herself paralyzed with inability, having attempted to make an arrangement but left only with cut pieces of once beautiful branches that were no longer usable. This incident profoundly affected her—she would continue to ask herself ‘why, why?’ not only immediately after but for years that followed.

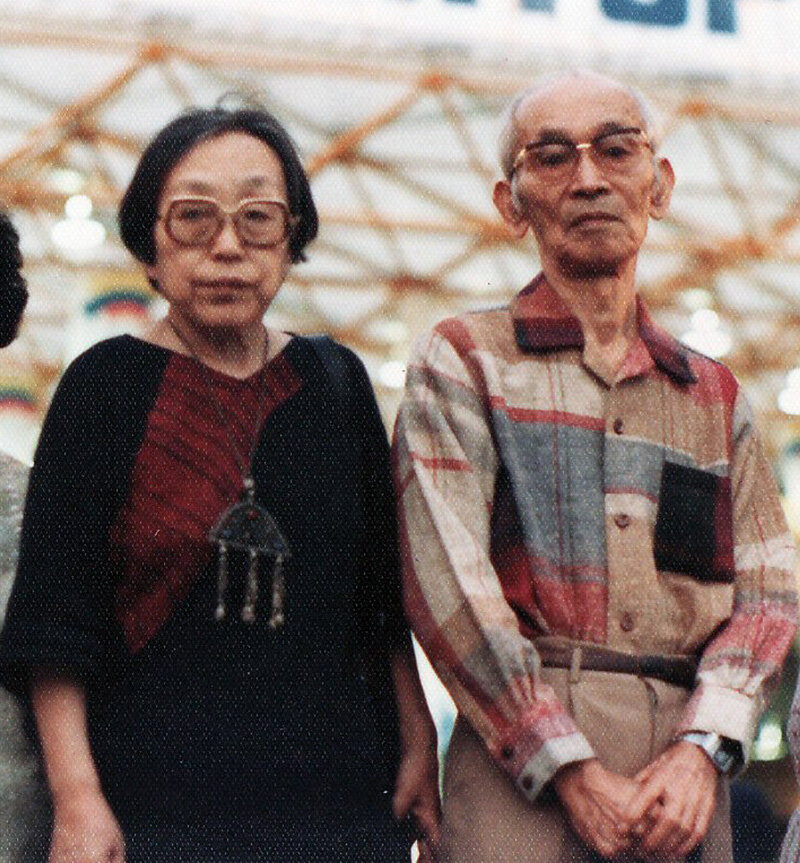

Misao and her supportive husband, Riichiro Jo, 1981.

The Art of No Teaching

Later, as the aerial attacks on Japan increased during World War II, Misao evacuated with her three, young sons to a remote village in the mountains, where they stayed for three years. During this time, she committed herself to actively exploring and developing a radical approach to flower arrangement. After returning to her hometown at the end of the war, word about her unique approach spread, and she was eventually invited to teach regularly in the local high school.

Whenever Misao conducted a class, she never made any samples for her students to follow. Contrary to the approach practiced in many traditional art forms, which encouraged students to imitate samples presented by instructors, she strongly believed that imagination should come from students, not teachers. And so, she developed a new approach: not teaching in a conventional sense but rather guiding and drawing out the individual sensibilities that already existed within each student. Although seeming inactive in a way, this approach of not teaching was very challenging and required close observation, attention and ingenuity.

“...imagination should come from students,

not teachers.”

Facing life’s obstacles

Word continued to spread about Misao and her innovative ikebana classes, and she began to teach in other schools and establishments. She devoted herself completely to her mission of developing genuine creativity and cultivating the unique sensibilities that she believed everyone inherently possessed. One day in 1954, Misao was preparing to conduct one of her classes, despite her husband’s concern due to an approaching typhoon. Just as she was leaving the house, she coughed and soon after realized that she had caught tuberculosis, which was extremely prevalent in Japan at the time. This diagnosis crushed Misao, as it presented a serious roadblock in the path of pursuing her dream. Even after she fully recovered her health two years later and many insisted that she start teaching again, saying no one could guide like she could, she did not dare to jeopardize her health and burden her family again.

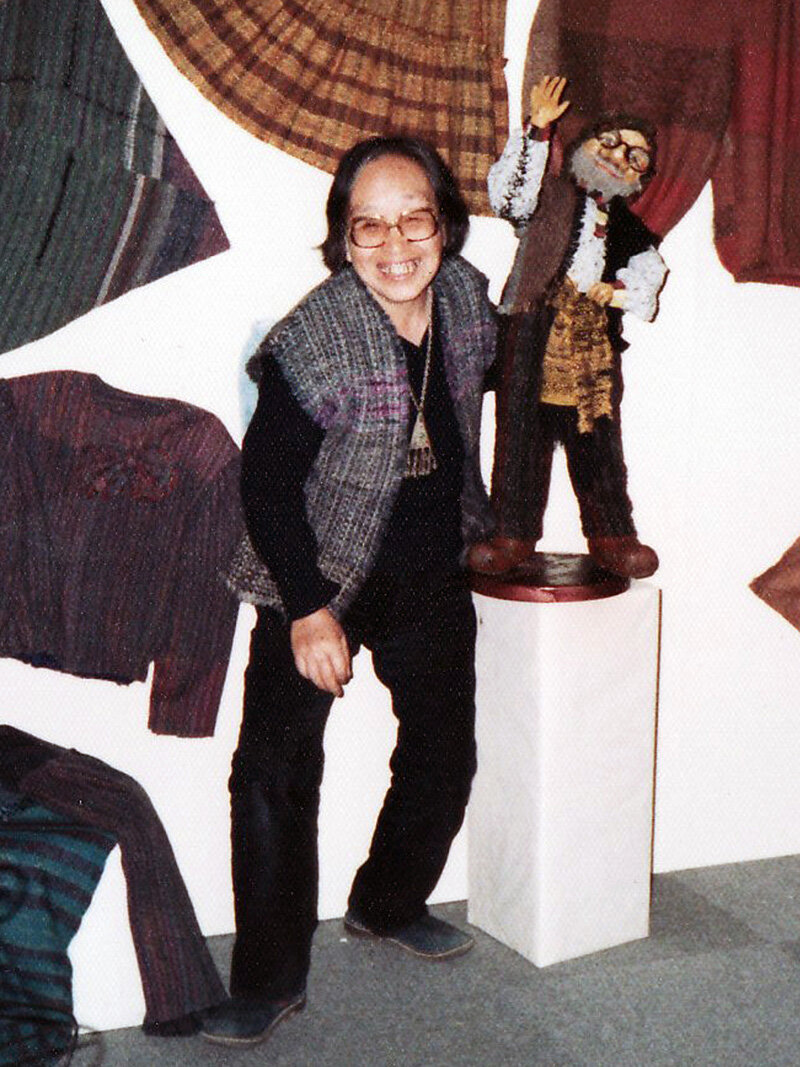

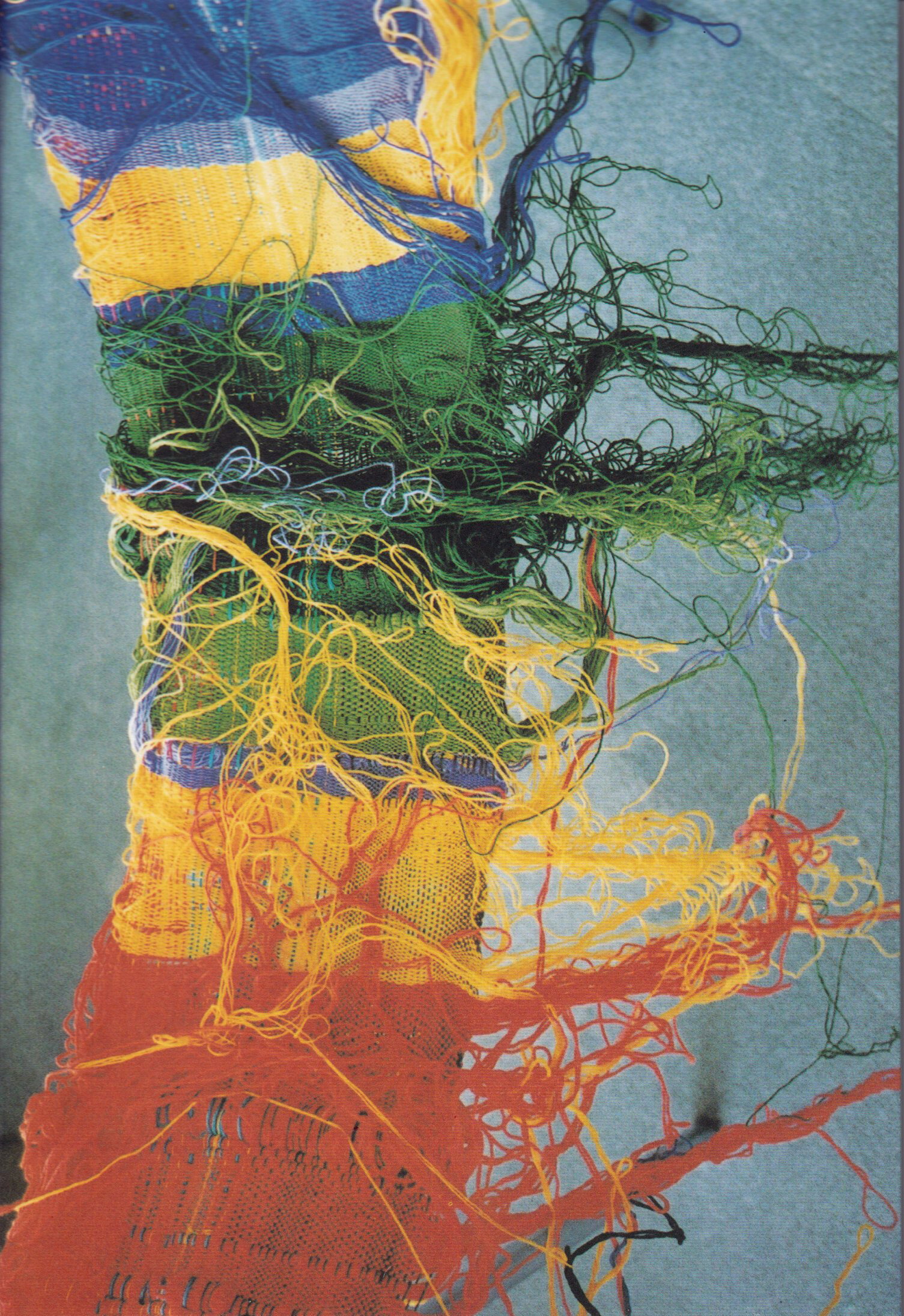

The first obi Misao wove at the age of 57.

Redefining ‘flaws’

Almost twenty years after Misao stopped offering her ikebana classes, her mother, who had previously earned a living as a weaver in a textile factory, was interested in weaving again for her own pleasure. It also happened that Misao herself wanted to weave a new obi sash for her kimono, which she was wearing daily at the time. So, together with the assistance and support of her family, Misao built a loom and wove for the first time at the age of 57.

In the first obi she wove, she discovered that a warp thread was missing. When she showed the sash to a man who ran a weaving factory in her neighborhood, he told her that it was ‘flawed’ and useless for that reason. However, Misao did not consider the missing warp thread to be a flaw but instead saw it as an element of beauty that occurred accidentally but she had chosen to embrace. She wanted to listen to her own inner creativity as opposed to simply imitating the conventions she and society had learned to value, such as the uniformity and predetermined quality of machine-woven cloth. Misao powerfully stated, “I have a brain and emotion. I am a human being. I will weave an obi that is full of humanity.”

From then on, she devoted herself to weaving cloth with ‘flaws’—cloth that only a human could weave and no machine could. She allowed and pushed herself to experiment, creating variations in the warp and weft threads in organic and unexpected ways. In doing so, Misao realized a sense of liberation and enjoyed herself more than she had ever imagined possible.

“I have a brain and emotion.

I am a human being. I will weave an obi that is full of humanity.”

Renewing her dream

When she showed her work to the owner of a reputable shop in Osaka, who highly praised and sold all of her pieces to her great surprise, she decided upon a name for her weaving: SAORI, a contraction in Japanese that means ‘Misao’s Weaving.’ Others continued to praise her weaving highly and the shop requested more and more pieces to sell, but Misao soon felt that this focus on the commercial value of her weaving caused her to lose the pleasure and freedom that she had previously enjoyed. She realized that she experienced joy when she remained faithful to her true self, spontaneous and unburdened by external measures of success or acceptance.

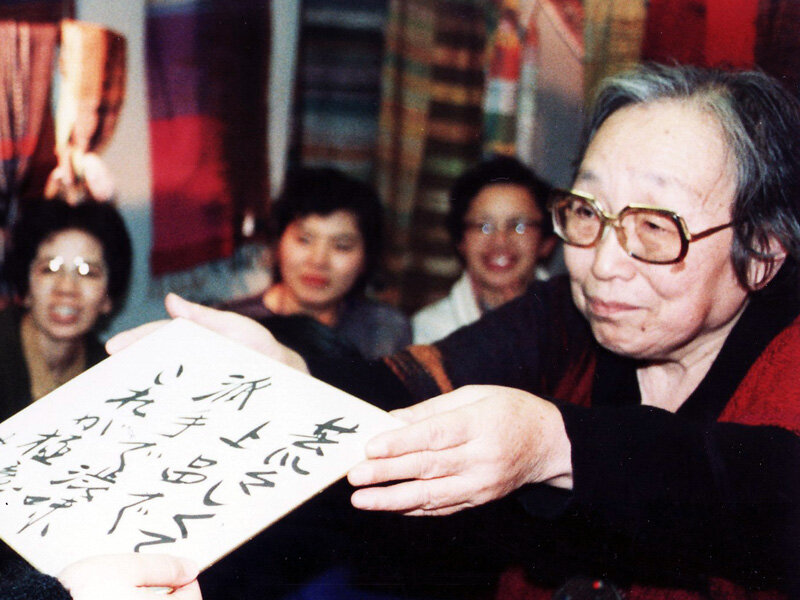

Contrary to what one might expect, Misao regarded the praise she received as a sign not of her own superiority but rather of the fact that everyone, like her, had something special hidden within and could express this unique and powerfully creative sensibility if given the opportunity and encouraged to break away from conventional ways of thinking. With this profound realization, in line with what she had already dedicated many years to with her practice of flower arrangement, she redirected her initial interest in weaving for personal hobby to a lifelong passion for deepening and sharing SAORI as an integrated practice of creative and personal realization made accessible through hand weaving. Misao connected the name SAORI to the Japanese word sai (差異), which means ‘difference amongst (not between) objects,’ to extend the significance of the name beyond herself and add a new meaning: ‘weaving individual dignity.’

Inspiring a movement

Misao firmly believed that through SAORI, others could develop a similar confidence and awareness about themselves and others just as she had. In order to support this vision, she and her family designed a new loom unlike any other, the very first SAORI loom from which all subsequent models have been developed. They had one primary goal: to create a loom that would be as easy to use as possible and best suited for all individuals to explore their creativity through free-flowing, uninhibited hand weaving.

In her classes and demonstrations, Misao always encouraged people to consider the differences between a machine and human being—to not imitate machine-made products but rather weave what only human hands and spirit can. She also emphasized the importance of respecting and inspiring one another within community and how practicing SAORI helps us to develop attitudes of mutual understanding and acceptance, which are indispensable for world peace and harmony. Just as no two human beings are identical, no two cloths woven by different people can be identical. Yet, they are connected by a shared life force, which cannot be measured or compared. SAORI Weavers practice the awareness that each moment, each cloth, and each human being are all different, uniquely beautiful and valued for what and who they inherently are.

“Just as no two human beings are identical, no two cloths woven by different people

can be identical. Yet, they are connected

by a shared life force, which cannot be measured or compared.”